Forty years ago, the minimum wage guaranteed a decent standard of living, including food, rent, and transportation. Now, Americans working just as many hours at the same pay level find these essentials almost out of reach. In forty more years, as automation continues to take root, it may be considered a privilege to even have a job, let alone afford the essentials. At the same time, the spectre of the super-wealthy looms over our society. The continued consolidation and automation of jobs benefit the same select few magnates, and the increasingly complex tax system makes it difficult to redistribute that wealth. It’s clearly time to re-level the playing field.

The Cliff Effect

“People view economic success and wellbeing in life as … a product of choice, willpower, drive, grit, and gumption,” says Nat Kendall-Taylor, CEO of FrameWorks. 1 “When we see people who are struggling,” he says, those assumptions “lead us to the perception that people in poverty are lazy, they don’t care, and they haven’t made the right decisions.”

Unfortunately, such assumptions don’t capture the whole picture. There is no place in America where a family supported by one minimum-wage worker with a full-time job can live and afford a 2-bedroom apartment at the average fair-market rent. 2 Moreover, the Government Accountability Office reports that 70% of the 21 million people receiving Medicaid or SNAP benefits work full time. 3 As the gap between cost of living and actual wages has grown exponentially, federal assistance programs have become a crucial safety net for working families across the country.

To qualify for assistance programs like Medicaid or SNAP, citizens must prove that they live at or below the adjusted federal poverty level. Given the political stigma surrounding investment in welfare programs, poverty levels are often set lower to target only those in serious need of assistance. For example, a family of three would need to make just $1,810 a month to qualify for SNAP, the equivalent of a 40-hour a week job paying just over $11. A $1 hourly wage increase could disqualify the entire family from their benefits.

These stringent conditions imposed upon such subsidies and benefits prevent people from rising up the economic ladder by inadvertently trapping their recipients under an income ceiling. These benefits, such as controlled rent, food assistance, and free childcare, are too materially valuable, so families pass up opportunities for advancement in the workplace to keep them, thus “staying in the same place on the cliff” to avoid slipping off.

Even while these workers might be staying put at the knife’s edge of benefits eligibility, the economy around them is constantly changing. Increased automation in factories has consolidated manufacturing jobs, while self-checkout systems in grocery stores now require employees to have some technical knowledge to assist customers. As market forces demand more skills or offer fewer hours, workers in the subsistence position find themselves stagnating or even falling behind. If they lose their job, they might be hard-pressed to find a new role.

Solution: An Income Floor

Minimum Basic Income, or an unconditional income floor, would allow people to grow without the fear of a steady income being taken away from them. Looking beyond a monthly scramble for money to pay for rent and food, people will be given crucial breathing room to improve their lives more tangibly. An unconditional source of income would serve as a crutch for people to actively improve their situation through education and skill-development without fear of losing that crutch through this process.

With Universal Basic Income (the umbrella term for unconditional federal aid) gaining popularity over the past couple of years, experimental trials have allowed us to gather data on the efficacy of the policy. The Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration or SEED is the first mayor-led income floor demonstration in America. Launched in February 2019 by former Mayor Michael D. Tubbs, SEED gave 125 randomly selected residents $500/month for 24 months. The participants were at or below Stockton’s median household income level of $54,614. 5

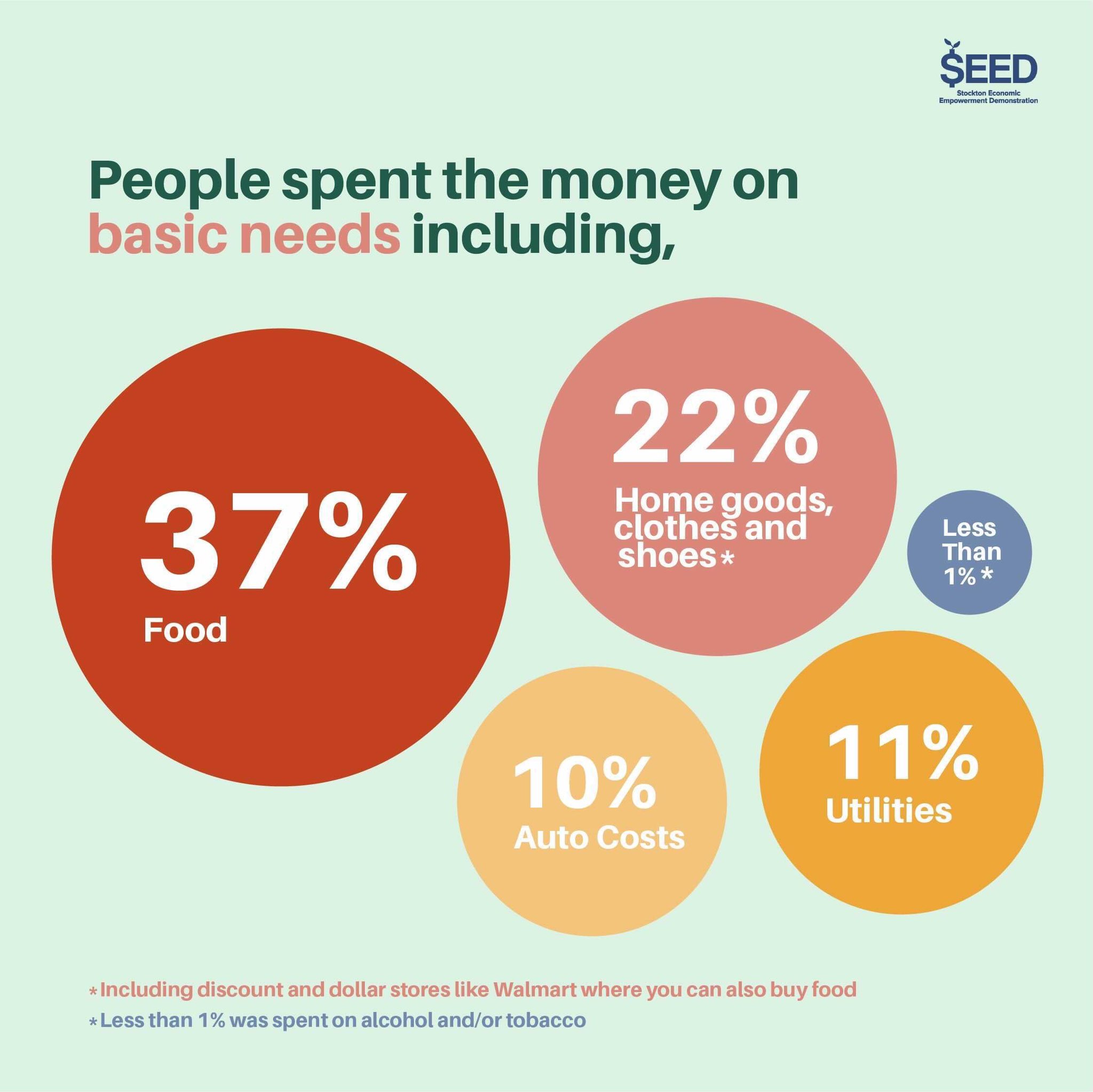

While research spanning the full trial will be released in 2022, the early qualitative and quantitative data available is very positive. Notably, almost none of the money was spent on restricted products like drugs or tobacco, contrary to the widespread misconception about the usage of donated money.

Additionally, those who received the monthly benefit went from part-time to full-time employment at more than twice the rate of those without the benefit, and recipients were also healthier, showing less depression and anxiety.

As one participant, Tomas, put it: “With the SEED money, there’s no need for the hustle. I have the time to actually sit there and actually take opportunities for myself, like if I felt like I wanted a new job or a different job, I was able to make it. I didn’t have to worry about it.”

Critics worried that people would be disincentivised to work when given unconditional handouts. 6 However, another study conducted in Finland supported the data in Stockton, refuting the critics’ assumption. 7 People on basic income worked an average of 78 days between November 2017 and October 2018, which was six days more than those on unemployment benefits.

An umbrella review by Stanford’s Basic Income Lab could find no evidence to support the critics’ worries. 8 The report, which compiled and critically examined 16 reviews on Universal Basic Income, concluded that “Findings are generally positive that UBI type programs alleviate poverty and improve health and education outcomes and that the effects on labor market participation are minimal.”

Other skeptics of UBI have raised that an income floor could reduce the number of workers doing necessary minimum-wage/unattractive jobs. By reducing people’s desperation for income, workers would be given the choice to weigh their wages against the job’s personal fulfillment. This could lower the number of participants in necessary menial labour.

Thankfully, automation can help fill in the gaps, increasing efficiency in the bottom rungs of the ladder without displacing people from jobs. This may sound futuristic, but it is well within our technological means to have a robotic foundation for the vast majority of minimum-wage jobs given their generally repetitive and algorithmic nature. Automated vacuums would clean our floors, checkout-free supermarkets 9 would make grocery shopping human-optional, and self-driving trucks could pick up our garbage, 10 all while we humans could spend our lives following more fulfilling, enjoyable careers.

For those who are permanently employed, Minimum Basic Income will not be sufficient to live on, as it’s not designed to replace jobs. However, with the economic progress driven by the lower-income population’s education, it is likely that new jobs will open up. Automation could also convert some demanding, full-time work into part-time and the income floor will step in to cover the gap in wages.

The Cost of a Minimum Basic Income

All this sounds utopian, but as always, one callously pragmatic question brings us crashing back down to reality.

Who will pay for it?

If an income floor of $500 a month is given to all Americans, it would carry a hefty federal price tag of $2 trillion annually. However, this isn’t much more expensive than the current welfare system, which encompasses roughly $718 billion at the state and local level 11 and $1 trillion through federal Social Security. 12

To prevent a potential inflation spike due to this massive cash infusion, we need to employ policy and economic tools in redistributing funds across the population. Just this week, House Democrats proposed a new tax plan to offset spending for their own ambitious $3.5 trillion spending bill focused on the social safety net. The plan calls for a top corporate tax rate of 26.5% and a top individual tax rate of 39.6%. Moreover, the proposal includes a 3% surcharge on individual income above $5 million and an increase in the capital gains tax to 25%. 13 Clearly, targeted changes to the tax code could yield major revenue to fund proposals like Universal Basic Income. If legislators are actually committed to reducing income inequality, progressive taxation is the perfect starting point.

Moving funds from the one-percenters to the rest by using the top bracket of progressive tax wouldn’t make too much of a dent in the wealthy’s pockets. It would even boost the overall economy, since “based on standard fiscal multipliers established by Moody’s Analytics, every extra dollar going into the pockets of a high-income American only adds about $0.39 to the GDP. By contrast, every extra dollar going into the pockets of low-wage workers adds about $1.21 to the national economy.” 14In context, if we applied this progressive tax plan to America’s 650 billionaires’ income during the pandemic and moved those funds into a Minimum Basic Income program, the GDP would be boosted by $300 billion. UBI payments will cycle back into the economy through increased consumption, supercharging the economy rather than stagnating it.

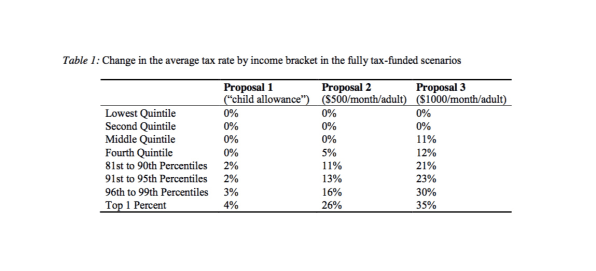

Academics have developed alternative models of taxation to fund UBI proposals. If income tax was enacted as shown in the table above provided by the Roosevelt Institute, the respective income floors would be funded for (“child allowance” refers to $250/month/child). 15 This zero-sum money transfer across the population “turns out to be a positive sum in the macro-simulation, thanks to the increase in aggregate demand and therefore in the size of the economy.” according to the same report’s brief.

While UBI would be a serious investment, it’s clearly a feasible one. More progressive taxation would surface the majority of the funds for the program, and a few years of deficit spending would yield major gains to the GDP and America’s industries.

Why now?

The pandemic has identified gaps in our public health infrastructure, our political system, and our society as a whole. The recovery could offer us a clean slate, a rare opportunity to refresh our policies on a deeper, more meaningful level, anticipating current and future economic issues rising with automation.

The distribution of stimulus checks shows that raising federal funds for widespread financial aid is logistically possible. 16 People have also used the money responsibly, despite the fact that the cheques were given to higher income households too.

“For all the talk of revenge spending and pent-up demand for travel, you wouldn’t know it by seeing just 13 percent of stimulus check recipients indicating that any of the money would be spent on discretionary activities or nonessential items,” said Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate. 17

As stimulus cheque usage could simulate how Minimum Basic Income would be used in practice by the American population, this responsible spending pumping money back into the system from the roots is highly promising.

Finally, unlike COVID-19, automation won’t be a surprise. In the midst of this economic disaster, we realised we have to prepare for the next one, making it especially key to legislate on automation-responsive social policies like UBI now.

The Verdict

UBI isn’t just an opportunity for recovery. It’s an opportunity for economic regeneration — to limit inequality, improve quality of life, and prepare our society for a more digital tomorrow. After decades of regression for America’s working class, Universal Basic Income would be a proactive step towards bold, poverty reduction rather than a retroactive attempt to provide the bare necessities. We won’t just be rebuilding the economy post-pandemic, but renovating it.